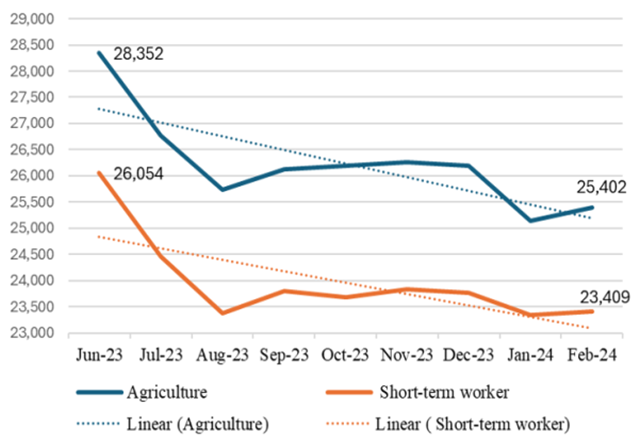

Evidence over nine months to the end of February 2024 shows a declining demand for Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme seasonal workers — those who used to be under the Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP), now absorbed into the PALM scheme as short-term PALM workers.

Figure 1 shows the monthly numbers of short-term PALM workers in agriculture and of all PALM workers in agriculture, between 30 June 2023 and 29 February 2024. (Now, under PALM, workers can be hired in agriculture on a multi-year, non-seasonal basis.)

The graph shows a decline of 10.2 per cent in short-term workers and 10.4 per cent for all PALM workers in agriculture. The latter figure reflects the sharper decline in long-term PALM workers in agriculture of 13.3 per cent, from 2,298 to 1,993. These declines are especially surprising because summer is the peak period for hiring agricultural workers.

Two factors are likely to be important in explaining this recent fall in PALM agricultural worker numbers: the growing number of backpackers seeking work in rural areas, and the new and more stringent PALM Deed of Agreement required for approved employers.

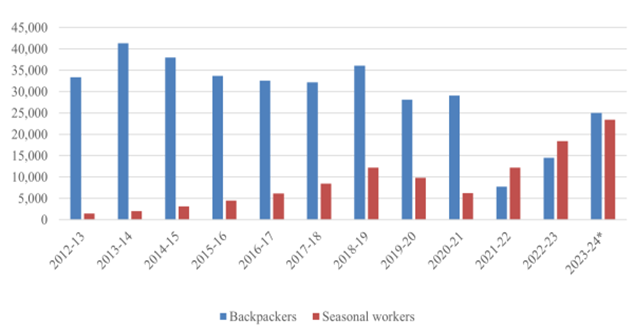

Working holiday maker (WHM) visa holders, more commonly known as backpackers, are the main alternative source of labour for growers to engage at harvest time. They are less expensive to employ because they are responsible for their own travel and accommodation costs. Official statistics for the period after Australia’s international border re-opened show that first-visa backpacker numbers have more than doubled to 175,599 in the 12 months to the end of the financial year 2022-23. The number of first-visa holders has continued to grow in the six months to the end of 2023, reaching 99,497 for the half-year.

There are also many more second- and third-year visa holders, that is, backpackers who have completed three months’ work in a rural area in their first year (to get a second-year visa) or six months in their second year (to get a third-year visa). In the financial year 2021-22, the number of these visa holders was only 11,643. But in the next 12 months to end June 2023, their number had risen to 26,421, and in the six months to end December 2023, their number has increased even more to 22,881. Projecting forward for the whole 12 months to the end of June 2024, the number of second- and third-year visa holders — extra temporary workers in regional areas – could reach nearly 46,000.

These statistics need to be adjusted to reflect the proportion of backpackers in rural areas working in agriculture. This has been declining owing to changes in government policy that have made other types of regional work eligible for visa extension. The details are provided at the end of this post, but I estimate that the number of backpackers working in agriculture in 2023-24 would be just over 25,000 (Figure 2).

The large increase in backpacker numbers (first, second and third-year visa holders) certainly suggests that these workers are replacing short- and long-term PALM workers.

The Australian government in June 2023 changed the PALM Deed of Agreement that employers must sign. A major change was to introduce a net minimum pay guarantee for every short-term PALM worker of 30 hours of work a week. From January to June 2024, this can be averaged over four weeks, but not after that.

In late 2023, the Approved Employers Association (AEA) and the Australian Fresh Produce Alliance (AFPA) surveyed larger labour hire firms and direct employers to ask them about the impact of the net minimum pay guarantee on future recruitments. In response, these SWP employers said they expected a reduced demand for short-term PALM workers of between 17 to 25 per cent, to manage the new financial risk and loss of flexibility.

By contrast to the decline in demand for agricultural workers, the number of long-term PALM workers not in agriculture over the same nine-month period shows a significant rise from 11,292 to 12,747 workers, an increase of 12.9 per cent. This confirms the problem that PALM has in agriculture. This is not only bad for the Pacific, but it will also increase worker exploitation, since it has been well documented that exploitation rates are higher among the lightly regulated backpackers than among the closely monitored PALM workers.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University. Richard Curtain is a research associate, and recent former research fellow, with the Development Policy Centre. He is an expert on Pacific labour markets and migration.